As the picture above half-jokingly illustrates, we have moved from an era of students as learners to the era of students as consumers, and we all know the customer is always right.

With colleges across the country changing their tune on standardized tests, a topic that has been building momentum for years is receiving more attention. The grades students have worked so hard for haven’t been carrying the same weight they once did. Enter grade inflation and the trend of rising average GPAs without corresponding increases in educational performance. In a misguided effort to motivate students, boost enrollment numbers, and avoid backlash, schools are distributing high marks with increasing frequency. This approach might make students and parents feel good in the short term, but it ultimately devalues the achievements of hard-working, talented students and fails to adequately prepare learners for future challenges. I see this truth often when I’m sitting in front of two 4.0 students from the same school but one has a 20 ACT score and the other has a 30 ACT score. Of course that doesn’t mean both students didn’t earn their respective As, but it does mean grades alone can’t paint a big enough picture of what type of learner they truly are. The one scoring 30 likely possesses greater reading comprehension and problem solving skill. He or she will also be able to handle different options in the classroom, particularly pace. Shouldn’t grades also be able to reflect these characteristics?

Research studies by ACT Inc. highlight both how grade inflation has outpaced performance in the classroom and test scores.

In the first figure below you can see both how Mathematics and Reading performance remained stagnant, while high school GPA continuously increased. In figure two you will also find average ACT scores on a slight downtrend during the same time period. This further supporting the idea that grades are now inflated.

Source: https://www.act.org/content/dam/act/unsecured/documents/2022/R2134-Grade-Inflation-Continues-to-Grow-in-the-Past-Decade-Final-Accessible.pdf

“This study supports the body of literature that has documented grade inflation for HSGPA across decades. While the findings are neither surprising nor controversial, they do indicate a persistent, systemic problem. One of the problematic situations that results in grade inflation is the variety of grading standards at high schools across the United States. HSGPA is a highly unstandardized measure of achievement because it incorporates not only content mastery or performance on an assessment but also many other factors including effort, participation, and educators’ personal impressions. In the college admissions context, this means that the 4.0 from one school may not indicate the same level of content mastery as a 4.0 from another school. This reduces the utility of HSGPA in evaluating college applicants. This is not to say HSGPA is not without merit. In fact, because it includes these additional, often non-cognitive and behavioral factors, it can provide predictive ability beyond that of content mastery alone.”

“The well-documented concerns about grade inflation across time and the non-achievement components in HSGPA result in an unstandardized and potentially problematic way to compare students across the country. A standardized comparison provides many benefits in contexts such as college admissions and scholarship applications. The standardized nature of the assignment of ACT scores ensures that a 36 for a student at a school with high grade inflation still means the same thing as a 36 for a student at a school with low grade inflation. This standardized metric provides a way to fairly and quickly evaluate students’ mastery of core content and potential for success in college. HSGPA and a standardized metric provide different information and therefore provide complementary information. For that reason, it is recommended that a holistic admissions evaluation, including both HSGPA and a nonsubjective metric, be used in conjunction when making decisions about college admissions as well as scholarship applications.”

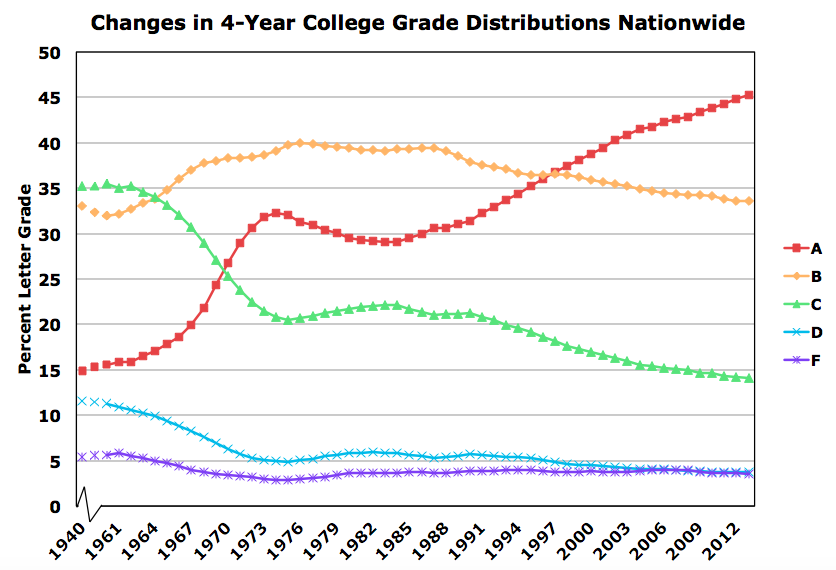

We have also seen this trend show up over many decades at the collegiate level. The percentage of As has been on the rise in a big way, and there is nothing over the last decade that suggests this pattern has slowed down.

Source: https://gradeinflation.com/

What may be causing this shift in high schools and colleges over the years?

Higher grades = fewer drop outs = more tuition paying consumers. As for the teachers and professors, keeping leadership and students happy via strong teaching evaluations = tenure and promotion. (Why Do Kids Get So Many As - Podcast)

America’s professors and college administrators have been promoting a fiction that college students routinely study long and hard, participate actively in class, write impressive papers, and ace their tests. The truth is that, for a variety of reasons, professors today commonly make no distinctions between mediocre and excellent student performance and are doing so from Harvard to CSU-San Bernardino. (gradeinflation.com)

While accepting the fact that the quality our students has improved over time, pressure to conform to the grading practices of one's peers, fears of being singled out or rendered unpopular as a 'tough grader,' and pressures from students were all regarded as contributory factors to grade inflation. (gradeinflation.com)

Student course evaluations are still used for tenure and promotion. High school grades continue to go up, which makes new college students less and less familiar with non-A grades. Tuition continues to rise, which makes both students and parents increasingly feel that they should get something tangible for their money. It’s not surprising that schools with the highest tuition not only tend to have the highest grades, but have grades that continue to rise significantly. (gradeinflation.com)

Unfortunately, the presence of grade inflation has weakened the value of student transcripts as a single measure of what students know or are able to do. So what does that mean for students working toward positioning themselves for college? Be prepared to demonstrate your skillset and academic strength outside of the boundaries of the classroom alone.